When is it right to admit your forecast is not accurate?

When is it right to admit your forecast is not accurate?

In terms of accuracy, many people claim that their forecast is very good – on average. In one tea manufacturing company I worked with the sales director claimed a 2% accuracy for his monthly sales forecast. The manufacturing director was less impressed because some individual products were 30% over, and some were half the forecast. The fact that they balanced out over the whole month and the whole product range did not make life easier in production

“Prediction is difficult, especially about the future” – Niels Bohr

Precision vs Accuracy

Precision vs Accuracy

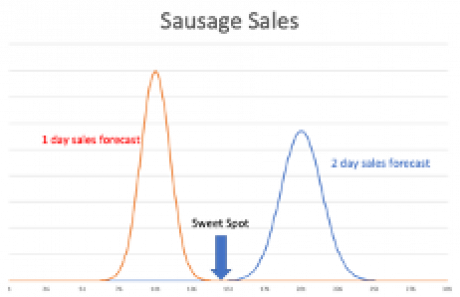

There are two key aspects to any business forecast and that is the precision and the accuracy of the forecast. These two terms are often, even usually, confused and I often must check which is which myself! An accurate forecast is close to the actual outturn; a precise forecast has a narrow spread and is more reliable. If I forecast sales for one day only, I could be amazingly accurate on that day but would know nothing about the precision. If I forecast sales every day for a year, I am likely to discover that on half the days my forecast was too high and half the days my forecast was too low. On many of these days, I will be close; on many of these days I will be way off. This spread, or precision, is often the most important aspect of business forecasting.

Aiming for the middle

Aiming for the middle

A military man I know once shared with me a technique they used when hiking across unknown territory. When walking across fields to hit a road going across their path which had a junction with another path or road which continued their journey, they would not aim for the junction directly. They would instead aim for a point 100 metres to the right of that target. When they reached the road, they knew they had to turn left to find their track. If they did not do it this way, then they often had to send scouts left and right to find out the correct direction to travel.

Most forecasting systems aim for the middle; they take the best forecast we have and base everything on that, but this is often a poor practice. At an airport I worked with they would forecast the number of passengers expected to arrive at security throughout the day based on flights leaving and the forecast was quite accurate (on average). This was used to plan the number of security lanes and number of staff required. However, on the days when

passengers arrived just a little earlier than expected there would not be enough security channels open, and queues would rapidly build. Once the queues are in existence then they

persist for a whole shift even though we have enough staff, on average, to process them! We see this effect in customer service / call centres all the time.

Sweet spot example

Sweet spot example

In a food company we worked with, manufacturing sausages, the best forecast of the demand from big retailers was made every day. Products were made in individual batches either one to two days ahead of order and despatch. When the quantity made was too low then another batch had to be made in a hurry which had a cost in labour and a cost in raw materials because of the set-up time and the material loss of cleaning down associated with each batch.

Making too much of the individual products also carries a risk. There is a two day “shelf life” beyond which the sausages cannot be shipped and must be thrown away wiping out the profit on a lot of sales.

But if we know, numerically, the PRECISION of the forecast though, we can find a sweet spot. Making a forecast of the range of volume for one day, and a forecast for the volume range of two days, we can calculate a figure which is greater than the MAXIMUM sales

expected for one day and less than the MINIMUM sales for two days. Forecasting the sales volume over two days is 30% more accurate than one day. This means that we will only manufacture a batch of each product once per day representing a big performance boost – we always have enough to satisfy sales and never throw anything away.

Psychology of forecasting

Psychology of forecasting

For more information or to book your exploratory consultation please call us on 020 7739 6565 or email admin@implementconsultancy.com

Forecasting demand is a crucial business skill and closely related to operational process design.

There is often a reluctance to acknowledge that our forecasts are not accurate (or not precise more often). It can feel like a criticism of our ability if it is our job to make forecasts. If we are dependent on someone else’s forecasts to manage our labour, service, or stock correctly then we can be quite vociferous in our opinions of the forecaster herself! This detracts attention away from us but does not fix the problem. Some things are more forecastable than other things; we need processes in place that routinely measure both the accuracy, and the precision of our forecasts, and the impact that this has.

Variability in demand

Variability in demand

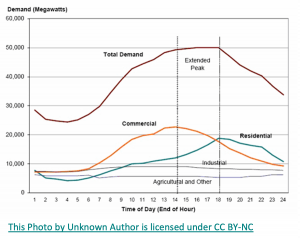

Real world forecasting is different from the rules used in textbooks and system developers’ models of the world. Usually, forecasts of our best-selling products are more accurate than the products that are less popular. It is easier to forecast the number of calls to our call centre at the peak time than at the off-peak time.

Having the same set of rules for every product (popular or not), for every time of day (peak or quiet) means we have something that is sub-optimal and yet this is how 90% of businesses work most of the time.

The costs of forecasting are often asymmetric. In some industries forecasting high is not a problem but forecasting low is inordinately expensive. In other industries the opposite is true. If we don’t put enough fuel on a plane, people could die, too much and the extra weight costs us in efficiency; if we don’t put enough ham sandwiches on the plane, we only have some lost sales or dissatisfied customers. If we don’t stock enough of a popular shampoo on a supermarket shelf the customer will just take another one or go elsewhere.

Every business needs to evaluate the value and impact that forecasting has on operations, and it is unlikely that popular systems (or even custom-built systems) will take account of these differences. A grocery chain might be proud of a stock turn of 26, carrying only two weeks stock on average but clearly there are differences across categories. Food salad items stock of two weeks is a disaster whereas this might be amazing in electrical items.

It is category targets however that can be the real disaster. When we set a target for anything – we are implicitly stating that motivation is the key to improving performance – but with stock there is an ideal level. Targeting below this will unbalance the process and increase costs whilst reducing service.

Across a category, there will be a pareto split of sales. 80% of sales will come from 20% of the products. The top 20% of products will be easier to forecast (more precisely) and can be replenished frequently, in smaller quantities, with confidence. The products in the bottom 20% of sales are far from this. We struggle to predict sales with any precision and any over ordering of product causes a stock build up that just will not shift. To compensate for this stock turn reduction, the stock planner will sail too close to the wind with the best-selling lines to make his targets and run out of stock for short periods of time.

The manager, the one who set the targets higher than the natural order of things, is disappointed to find that the stock turn is lower than the target he set, and the stock availability or service levels, are lower than the target. This is the exact opposite of what he hoped for, and he is likely to blame the stock planner, not himself. If you examine your sales and find that the pareto rule (or 80/20 rule) doesn’t fit very well (e.g., only 60% of sales come from the top 20% of products) then there is a good chance that you are suppressing sales of your best-selling lines. We use this test frequently in our Opportunity Review and often find that sales are depressed because best selling lines are out of stock or unavailable

Changing Operations

Changing Operations

So, what do you do if your forecasts are not accurate or not precise? The natural response is to try to improve the forecast. Building better IT systems with more processing power. Increasing the amount of information used. Perhaps we can use weather forecasts to better predict barbecue meat sales. Perhaps we can use traffic information to better predict passenger arrivals at the airport. Often though, none of these things will work. If we know the accuracy and the precision of our forecasts, then we can reconfigure our operations around this and increase profitability substantially.

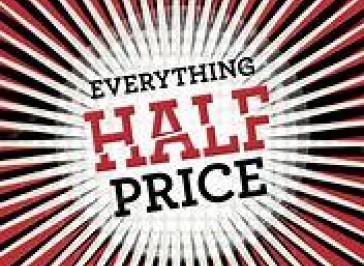

The clothing retailer Zara did this and was breaking all the retailing supply chain rules. Forecasting sales of a fashion garment six months out is tremendously difficult. Especially when broken down by size and by colour. This is exactly what a fashion retailer must do. They order the next season a long time in advance.

Zara realised this forecasting difficulty and changed their whole operation to one which was much more costly per item sold. Instead of six months they would shorten the time from idea to “in store” to 15 days (see here). They would deliver to stores twice per week; they would move product from a store where it did not sell to another store where it might. They would air freight products or ship half empty containers around the world. This huge increase in costs compared to other retailers should have seen their profits sink but instead they soared.

Perhaps the biggest cost in fashion retailing is the price markdown that takes place at the end of the season. Products – even popular ones – are sold at a discount of 30% or 50% or 70%. In avoiding this markdown cost, long accepted across the industry, Zara increased profitability and offered choice to customers and was rewarded with more frequent visits and purchases from its loyal fans.

Real world forecasting is always bespoke. Knowing the precision is more important than the accuracy and changing processes and operations to exploit or mitigate forecasting errors is the key to success.

Kieran Flanagan